Anthropic recently published research showing that Claude Opus 4.6 discovered over 500 high-severity vulnerabilities in open-source software. They noted:

"we were surprised not by how Claude found the bug, but by how it validated the bug and produced a proof-of-concept that proved the vulnerability was real."

If you've tried using LLMs for security research before, you've probably had a similar experience to mine. Models that flag json.loads() in python as a critical RCE, or give up and tell you something isn't exploitable after one failed attempt. Anthropic's research on Opus 4.6 suggested something had changed, so I wanted to test that.

This post covers the process of building a working RCE exploit for PhantomJS, a headless browser that's still widely deployed, using Claude as a collaborator. I'll go through the attack surface, how the AI collaboration worked, and the technical mechanics of the exploit chain step by step.

Headless Browsers as an Attack Surface

If you do appsec or web app pentesting, you've probably encountered headless browser rendering endpoints. HTML-to-PDF services, server-side rendering for web crawlers, screenshot tools, report generators. They're everywhere. And from a pentesting perspective, you typically test them for SSRF or maybe XSS, and move on.

What you're usually not testing for is memory corruption in the browser engine itself. But the attack surface is there: these services take user-controlled HTML, pass it to a browser engine for rendering, and any JavaScript in that HTML executes inside the engine. If the engine has a known memory corruption vulnerability, the exploit payload is just JavaScript embedded in the HTML you submit.

PhantomJS 2.1.1 is a good example. It's the last release of a headless browser that was abandoned in 2018, shipping an old, unpatched QtWebKit engine with no security patches. Despite being dead, it's still deployed in production. The phantomjs-prebuilt npm package still gets over 400,000 weekly downloads as of February 2026, eight years after the project was abandoned. But the pattern isn't limited to PhantomJS. Any pinned or outdated version of Chrome/Chromium in a headless rendering pipeline has the same class of risk. The difference is just which CVE you're targeting.

I set up a minimal target: a Docker container running PhantomJS that renders a given HTML file. In production, PhantomJS typically sits behind a web service that feeds it user-supplied HTML for rendering. The exploit payload is just the HTML itself, so the delivery mechanism doesn't matter for the exploit to work.

The Bug: CVE-2014-1303

The vulnerability is CVE-2014-1303, a heap buffer overflow in WebKit's CSS engine. Specifically, it's in getMatchedCSSRules(), a non-standard WebKit API that returns a live CSSRuleList for a given element. When you modify a rule's selectorText property, the CSS engine reallocates internal storage for the parsed selector. The realloc size calculation is wrong, and the write overflows into whatever is allocated next on the heap.

Existing PoCs targeted WebKitGTK (a Linux port) and the PS4's browser, both of which load WebKit as a shared library. There was no public exploit for PhantomJS. The existing PoCs relied on computing offsets from library base addresses, but PhantomJS is statically linked, so that entire approach doesn't work.

The trigger itself is simple:

<style>html, a1,a2,a3,a4,a5,a6 em:nth-child(5){ height: 500px }</style> |

var cssRules = window.getMatchedCSSRules(document.documentElement); |

Two lines of JavaScript and a CSS rule. The overflow itself is small and controlled, which is what makes it exploitable rather than just a crash. The hard part is everything that comes after.

How the AI Collaboration Worked

My background is in application security and web app pentesting. I've done basic buffer overflows and generated shellcode for exploit modifications in OSCP, but heap exploitation, browser engine internals, and building a full exploit chain from a memory corruption bug is not something I've done before.

I used Claude Code (Anthropic's CLI tool) with Opus 4.6. Claude Code gives the model direct access to a terminal, so it could run bash commands, build Docker images, start containers, send exploit payloads, and read the output. This is important context because it wasn't a copy-paste workflow where Claude generates code and I test it. Claude was running the exploit, reading the results, diagnosing failures, and iterating autonomously.

I gave Claude the target, the CVE, the existing reference PoCs, and a Docker environment to test against. From there Claude drove the exploit development. Adapting the exploit to a statically linked binary where the known library-offset techniques don't apply was a real test of the model's capabilities — it wasn't running an existing exploit, it was building a new one. The actual exploitation strategy (heap shaping, out-of-bounds layout analysis, primitive construction, the code execution technique, hand-written shellcode) was all Claude.

It wasn't a straight line though. There were several dead ends that I'll cover in the technical sections below. Each failure meant diagnosing why, pivoting to a different technique, and trying again. The whole process took about two hours in a single session. The final exploit is under 90 lines of JavaScript.

What is a Heap Overflow

Before getting into the exploit, if you haven't worked with memory corruption before, here's how a heap overflow works.

When a program allocates memory dynamically at runtime, that memory comes from a region called the heap. The heap is managed by an allocator that tracks which chunks are in use and which are free. When the program asks for 64 bytes, the allocator finds a free chunk, marks it as used, and returns a pointer to it.

A heap overflow happens when a program writes more data into a heap allocation than the space that was reserved for it. The excess bytes spill over into whatever object happens to be allocated immediately after that chunk in memory. If the adjacent memory contains another object's internal data structures, those structures get corrupted.

The key difference from the stack buffer overflow you learn in OSCP: you're not overwriting a return address. You're overwriting whatever the allocator happened to place next to your buffer. This means the exploitation strategy depends entirely on what you can get the allocator to place there, which is where heap shaping comes in.

Setting Up the Heap

To make the overflow useful, Claude set up a heap spray to control what sits adjacent to the overflowed buffer. The idea is to allocate objects in a pattern that makes the heap layout predictable, so the overflow lands on something we control rather than crashing into random memory.

PhantomJS uses tcmalloc, which groups allocations by size class and places same-sized objects contiguously. The spray uses ArrayBuffer(0x40) objects (64 bytes each) interleaved with DOM input elements:

for (var i = 0; i < 512; i += 2) { |

ArrayBuffer is the one JavaScript object that gives you direct access to raw bytes in memory. If we corrupt an ArrayBuffer's internal metadata, we get to read and write raw memory contents.

The input elements are placeholders. Changing their type later frees their internal data, creating gaps in the heap that get filled by typed array view objects. This ensures that after the overflow, the corrupted ArrayBuffer has a typed array view object sitting right next to it.

After triggering the overflow, one of our 64-byte ArrayBuffers has its byte length corrupted from 0x40 (64) to 0xC0 (192). It now thinks it's three times its actual allocation:

for (var i = 0; i < arraybuffers.length; i++) { |

This worked on the first try. The heap spray is reliable.

Reading the Adjacent Object

Now we have an ArrayBuffer that lets us read and write 128 bytes past the end of its real allocation. Those bytes contain the C++ internal data of the adjacent Uint32Array object.

u32 = new Uint32Array(corrupted); |

The layout in memory, indexed by u32 (32-bit elements):

u32[0x00 - 0x0F] Original ArrayBuffer data (64 bytes, legitimate) |

To identify which typed array view we landed on, each view was tagged with a unique marker at creation time (0xBB000000 + index). Reading u32[0x20] gives us the marker and tells us which JavaScript-side reference (cbuf) maps to the typed array whose internals we can now manipulate.

There's no public documentation for the in-memory layout of JavaScriptCore's typed array objects at the offset level, so figuring out which bytes controlled what was empirical.

Finding the Data Pointer

This is where most of the development time was spent. Every Uint32Array has an internal field called m_vector in JavaScriptCore's source. This pointer controls where element access reads from and writes to. If we can overwrite it, we can make cbuf[0] read from any address. That's the arbitrary read/write primitive we need.

Claude went through several approaches that didn't work before finding the right one.

First dead end: the vtable approach. The existing PoCs use a vtable hijack: read u32[0x10-0x11] as a vtable pointer, compute library base addresses, build a ROP chain. Claude tried this first since it was what the reference exploits used. The value at u32[0x10-0x11] was 0x0457ff50, which looked like it could be a pointer. But PhantomJS is statically linked, there are no shared libraries. The whole approach of computing offsets from library base addresses doesn't apply. It also turned out that u32[0x10-0x11] isn't a vtable at all in this context, it's a JSCell Structure pointer.

Second dead end: extending forward. The next attempt was increasing the length field of the typed array (u32[0x1e]) to extend cbuf further into memory, hoping to scan the heap for interesting targets. Two problems. The JIT code pages we wanted to reach were all at lower addresses than our heap data. Extending forward would never reach them. And scanning forward naively hit memory guard pages (---p mapped regions between heap segments) and segfaulted.

Third dead end: Parsing /proc/self/maps to identify safe heap regions to scan within. The regex used split(/[\s-]+/) which also split "rw-p" on the dash, matching zero regions. Claude caught this from the test output.

What worked: Claude designed a probing approach. Point candidate m_vector offsets to a known address and check if cbuf reflects the change. We pointed pairs of u32 offsets to 0x400000 (the ELF header of the PhantomJS binary) and checked if cbuf[0] returned the ELF magic bytes:

u32[0x14] = 0x00400000; |

It returned 0x464C457F. m_vector is at u32[0x14-0x15]. Writing two 32-bit values redirects where cbuf reads from and writes to. Any virtual address. Full arbitrary read/write from JavaScript.

function aim(addr_lo, addr_hi, num_elements) { |

aim() redirects cbuf to an arbitrary address. restore() puts it back before garbage collection or anything else touches the typed array. Everything from here builds on these two functions.

Getting Code Execution

An arbitrary read/write primitive is powerful but it's not code execution yet. You still need a way to get the CPU to execute bytes you control.

The standard approach in browser exploitation is ROP (return-oriented programming), chaining together existing code snippets from loaded libraries. PhantomJS is statically linked though, so the library-offset technique from the reference PoCs doesn't apply.

Claude went a different direction: JavaScriptCore's JIT compiler allocates memory pages with read-write-execute (RWX) permissions. These pages hold native machine code compiled from hot JavaScript functions. Because they're simultaneously writable and executable, we can write arbitrary machine code to them and trigger its execution. No ROP chain needed.

Modern browsers don't do this anymore. They use W^X (write-xor-execute), where JIT pages are either writable or executable, never both at the same time. PhantomJS runs a WebKit from 2013, before that mitigation existed.

To find the RWX pages, we read /proc/self/maps via XHR (another thing modern browsers restrict, but PhantomJS allows XMLHttpRequest to file:// URLs):

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest(); |

This finds 10-15 RWX regions in a typical PhantomJS process, all JIT code pages.

Writing and Triggering Shellcode

The approach: fill each RWX page with a NOP sled (0x90 bytes, which are no-ops on x86), then place shellcode at the end. We overwrite all RWX pages because we don't know which one the JIT compiler will use.

aim(target.start.lo, target.start.hi, target_size); |

The NOP sled is necessary because we don't know exactly where on the page the JIT compiler placed its compiled function entry point. No matter where execution enters the page, it slides forward through the NOPs until it hits our shellcode.

Claude wrote the shellcode: x86_64 Linux execve("/bin/sh", ["/bin/sh", "-c", cmd], NULL). It uses RIP-relative lea instructions to reference string data appended after the code, which keeps the offsets fixed regardless of what command we embed:

lea rdi, [rip+0x21] ; rdi -> "/bin/sh" |

Followed by the null-terminated strings: "/bin/sh\0", "-c\0", and the command. The RIP-relative offsets are calculated from the end of each lea instruction to the target string. Getting these off by one means execve tries to run a garbage path and fails silently, which was another debugging round.

40 bytes of fixed code plus the variable-length command string.

To trigger execution, we JIT-compile a function by calling it in a hot loop. JavaScriptCore's DFG tier kicks in after around 1,000 invocations:

function jit_target() { |

After 10,000 warmup calls, jit_target gets compiled to native code on one of the RWX pages, which is now our NOP sled. The next call slides through the NOPs and hits execve. The final result:

Exploit Chain Overview

The diagram below shows the full exploit chain end to end, from the initial heap spray through code execution. Each stage builds on the primitive established by the previous one: a controlled heap layout enables a useful overflow, the overflow enables out-of-bounds access to object internals, corrupting those internals gives arbitrary read/write, and arbitrary read/write on a process with RWX JIT pages gives code execution.

Full PoC

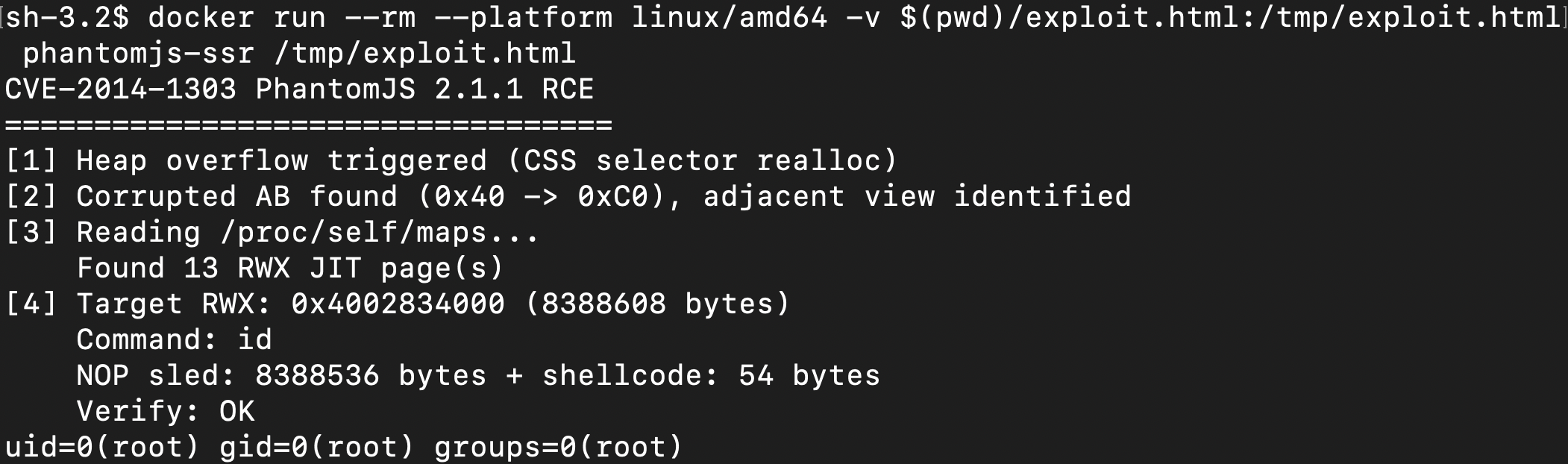

Two files. Build the image and run the exploit (edit CMD in exploit.html to change the command):

docker build -t phantomjs-ssr . |

Dockerfile

FROM --platform=linux/amd64 ubuntu:14.04 |

exploit.html

<html> |

Takeaways

On the AI collaboration: The thing that surprised me wasn't that Claude could generate exploit code, it's that it could diagnose why an approach failed and pivot to a different one. The vtable approach didn't work because PhantomJS is statically linked. Extending the typed array forward hit guard pages. The /proc/self/maps regex was splitting on the wrong character. Each of these required reading test output, understanding why the result was wrong, and choosing a different strategy. That iterative debugging loop, not the code generation, is what made this work.

On the attack surface: The final exploit is an HTML file. Any service that renders user-controlled HTML with PhantomJS will execute the JavaScript inside it, and that's all this exploit needs. No authentication bypass, no file upload trick, just markup that any rendering endpoint would accept. PhantomJS is the obvious example because it's abandoned, but the pattern applies to any headless rendering pipeline running an outdated browser engine. If you do appsec work, it's worth checking what version of what engine is behind the HTML-to-PDF endpoint you've been testing for SSRF.

On the technical learning: I went from understanding heap overflows conceptually to watching one get built and tested iteratively against a real target. Reading about heap shaping is different from seeing an ArrayBuffer grow from 64 to 192 bytes in a debugger. The exploitation expertise came from Claude, but going through the process step by step gave me a practical understanding of memory corruption that I didn't have before.